The European Union wants to listen in on our conversations again

Imagine this situation: you send your wife a photo of your child in the bath, who has amused himself by making a foam cap on his head. Instead of enjoying the moment and your child's happiness, you end up in prison for distributing pedophile photos.

Or imagine this situation: Your child has a worrying rash. You take a photo to send it to your doctor via instant messenger. Or another scenario: you send a friend a “dark humor” meme that is funny among your circle of friends, but taken out of context, it looks terrible. Or maybe you're just writing to a friend about your health, financial, or relationship problems.

You do this on a private, encrypted messenger, believing that this conversation will remain between you. It's like closing your bedroom door and drawing the blinds.

Meanwhile, in Brussels, the fate of regulations that could break down these “digital doors” and render “privacy” nothing more than an empty slogan in history books hangs in the balance. We are talking about Chat Control.

This is a topic that has been coming back like a boomerang since 2020, when the first attempts to implement it appeared, albeit in a different form and under a different name. In the name of the safety of our youngest, should we agree to have a machine looking over our shoulder every time we pick up our phone?

Table of Contents

What is this really about?

Officially, it is called “Regulations on the prevention and combating of sexual abuse of children.” The goal is noble, and no one in their right mind would argue with it: we must fight child pornography and the sexual abuse of minors (CSAM - Child Sexual Abuse Material). It is a scourge and must be burned out with iron and hot tar.

The problem lies in the method that some EU officials want to use.

The proposed regulations (commonly referred to as Chat Control) stipulate that service providers such as Facebook (Messenger), WhatsApp, Signal, and email providers would be required to detect and report suspicious content.

Sounds reasonable? Yes, but as is usually the case, the devil is in the details. In order to find “suspicious content,” the system must “see” all content. This includes content sent by you, your grandmother, your teenage son, or the CEO of a bank.

From the point of view of cybersecurity and civil liberties, this introduces a presumption of guilt. Each of us becomes a suspect until the algorithm determines that our message is “clean” and allows it to fly on to the recipient. This is not a surgical strike aimed at criminals. It's casting a net across the entire ocean to catch a few specific fish, suffocating all the others in the process.

What about encrypted communication?

Currently, secure messaging apps (such as Signal or WhatsApp) rely on end-to-end encryption (E2EE). This means that the message is encrypted on your phone and decrypted only on the recipient's phone. No one in between—neither your internet provider, nor the app owner (e.g., WhatsApp), nor cybercriminals, nor even the government—can see the content. They only see digital gibberish. WhatsApp, nor a cybercriminal, nor even the government – can see the content. All they see is digital gibberish.

Introducing Chat Control in its proposed form would require circumventing this security measure. How can this be done technically? There are ways to do this, and they are all disastrous for your security:

- Client-Side Scanning: This is a scenario in which your own phone becomes an informant. Before the message is encrypted and sent, a special module in the application or even in the operating system scans the photo or text. If the algorithm (AI) decides that something is wrong, it sends a report to the authorities. Encryption continues to work, but the damage has already been done before the message is sent.

- Backdoors: This forces application developers to create a special “universal key” for the authorities. It's as if every door lock in Poland had one state-owned key that fits everywhere. Encryption still works, but one entity can bypass it. Just like that, entering through the back door.

- Weakened Encryption: It's a “silent killer” method. Instead of breaking down doors, manufacturers are forced to install plastic locks. The EU can force suppliers to use older or deliberately weakened encryption algorithms that the authorities can already crack (because they have enormous computing power). For the user, “the padlock in the app will still be green,” but in reality, the security will be illusory. This is a return to the dangerous ideas of the 1990s, when governments tried to limit the power of civilian cryptography.

In each of these cases, the essence of private conversation ceases to exist. As experts and even the European Court of Human Rights rightly point out, mass scanning cannot be reconciled with the right to privacy. Either we have strong encryption and privacy, or we have Chat Control. There is no middle ground.

Technology is wrong... often

Supporters of this solution say: “Don't worry, artificial intelligence will do it, no one will read your messages unless the AI finds something.”

If it's going to be done automatically, what could go wrong? A lot of things.

False Positives

AI algorithms do not understand context. They are trained on patterns (it is interesting how and where they got these patterns from...), but they get lost in the nuances.

- A photo of a child on the beach sent to grandparents? The algorithm may consider it pornography.

- An innocent joke, a meme, or a sarcastic exchange with a friend? The algorithm may consider it grooming.

This is not a theory. It is already happening.

I am referring to the story of a father from San Francisco (described in the media as “Mark”) whose Google account was blocked after the anti-CSAM system identified photos of his sick child sent to a doctor as child pornography.

In February 2021, during the pandemic, a nurse asked parents for photos of their young son's private parts due to a suspected infection so that a doctor could view them before a teleconsultation; the photos were taken with an Android phone and a copy was automatically sent to Google Photos.

Google's algorithms for detecting CSAM material flagged these photos as potentially illegal; after verification by a moderator, the company blocked the father's account, searched the rest of his data and, in accordance with US law, reported the case to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, which triggered a police investigation in San Francisco.

Mark was investigated on suspicion of child abuse, but fortunately, after analyzing the material, the police concluded that no crime had been committed and dismissed the case.

Unfortunately, despite being cleared of the charges, Google did not restore access to the account: the man from San Francisco lost his emails, contacts, photo copies, location history, as well as access to his Google Fi number and other services dependent on the account; his appeals, including the attached police report, were rejected.

Do you think this is just one isolated incident? The second case involved a father from Houston, Texas, described in the media as “Cassio.”

In the world of Chat Control, this could happen to any of us. You will have to prove to the prosecutor that you are not a criminal because the algorithm made a mistake.

A gift for cybercriminals

In cybersecurity, there is a simple, brutal rule: if there is a “back door” or weak point in the system for the good guys, sooner or later the bad guys will find it too.

Service codes and factory passwords are a perfect illustration of this problem. The history of IT is full of cases where manufacturers—from hotel safe makers to web application developers—left “back doors” in their systems. These were often simple, undocumented passwords (so-called hardcoded passwords) or service codes intended to provide technicians with emergency access (e.g., when a hotel guest forgets the code to their safe).

In theory, they were supposed to help. In practice? These codes leaked onto the internet, and instructions on “how to open any model X safe” went viral, giving thieves a universal key.

Exactly the same thing will happen with the “backdoor” in your messenger. If a key is created for the police, sooner or later it will fall into the hands of cybercriminals or foreign intelligence services.

Abuse of power, or the normalization of deviance

The greatest risk, although not immediately apparent, is a psychological mechanism called normalization of deviation. Diane Vaughan described this phenomenon while investigating the Challenger shuttle disaster. It is a process in which we gradually accept standards that would previously have been unthinkable, simply because “it worked last time” and there was no disaster.

A great example is my hobby, diving. Imagine a diver who once bent the safety rules—he dived deeper than he should have or with less gas. Did he come up? He did. Nothing happened. The brain gets the signal: “These rules are exaggerated, they can be circumvented.” The diver does it a second time, a third time... Until this risky behavior becomes the new norm for him. The question is: how far can you go before you get carried away or, worse, run out of gas and die?

It's similar with Chat Control.

- Today, we agree to CSAM scanning. The deviation from the privacy standard is accepted.

- Tomorrow, the government will say, “Since the system is already in place, why don't we scan for terrorism?” And we will agree again, because it's the new norm.

- The day after tomorrow: “Let's check who isn't paying taxes.”

- In a year: “Let's see who is organizing the protests.”

- And so on.

We don't break the rules suddenly—we simply push the boundaries of acceptance. Instead of asking, “Why should we invade privacy?”, we start asking, “Why shouldn't we, if it helps?”. In this way, step by step, without much fanfare, we get used to living in a glass house.

Criminals will manage anyway.

This is the biggest paradox. Real, organized criminals are not stupid. If WhatsApp or Messenger start scanning messages, criminals will simply switch to niche, open-source messengers, their own servers, or solutions outside the European Union that are beyond the reach of the law. So who will this law affect? Ordinary citizens. You, me, your company. We will be stripped of our privacy, while criminals will laugh in our faces, using their own secure channels.

Technology cannot be “uninvented” (The Genie is out of the bottle)

There is another fundamental problem: mathematics cannot be banned. Encryption algorithms (such as AES or RSA) are common knowledge. They are like the wheel—once invented, they will not disappear, even if someone bans their use.

If the European Union forces popular messaging apps to use, for example, “weaker,” flawed encryption, one thing will become obvious:

- Criminals: They will hire programmers who will create their own messenger in a week, based on the “old,” good, and secure open-source algorithms. They will do this outside of app stores, outside of EU control, without backdoors. They will be safer than ever before.

- You, the “average Joe”: You will stick with the “legal,” buggy messenger because you don't have the knowledge or time to set up your own servers. Your data—from photos of your children to scans of your ID cards and bank passwords—will be sent through a channel that has been deliberately weakened.

As a result, we will create a system in which only criminals have the right to privacy, while honest citizens are exposed to surveillance and attacks by cybercriminals.

How to protect your digital privacy?

The situation is dynamic. Poland (fortunately!) is among the countries that are vocally opposing these regulations in their current form, but the pressure in Brussels is enormous. Regardless of what politicians decide, you need to take care of your digital hygiene.

Choose your instant messengers wisely

Use apps that prioritize privacy and openly state that they will not scan your content.

- Signal - The foundation behind Signal has already announced that it would rather withdraw from the EU market than break its security rules and introduce scanning. It is currently the “gold standard” for ordinary users.

- Threema - A Swiss messenger app, paid (which is an advantage, because you are the customer, not the advertiser), which does not even require a phone number.

Educate yourself and others

Awareness is key. Talk to your friends and family. Explain to them that encryption is not about “hiding something bad.” It's about digitally locking the doors to your home and covering your windows. It's your right to privacy.

Respond

You can influence the law. You can write to your local MEPs to express your opposition to mass surveillance. Organizations such as EDRi (European Digital Rights) and the Polish Panoptykon Foundation are running campaigns that you can join.

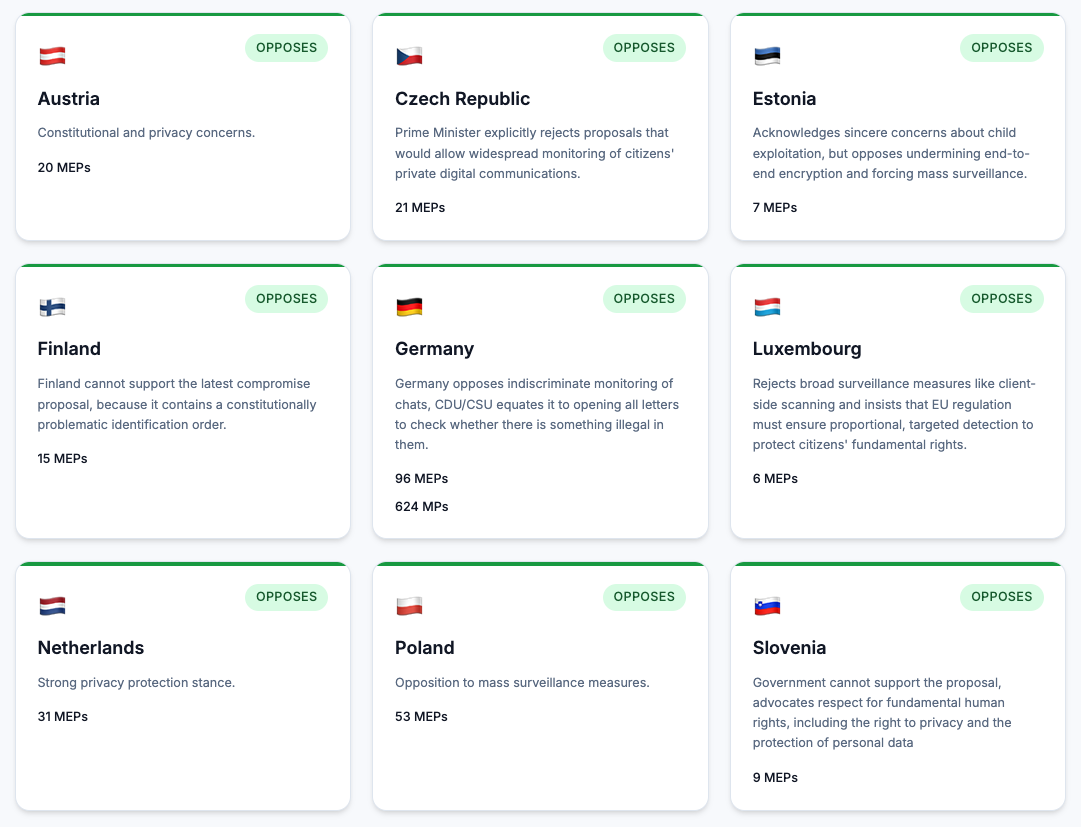

You can also do this via the website fightchatcontrol.eu, where you can check which countries support Chat Control and which do not.

National solutions – how to report illegal content?

It is worth knowing that we are not helpless and do not have to wait for controversial EU regulations to combat CSAM. Effective, secure mechanisms are already in place in Poland, supported by the Ministry of Digital Affairs and NASK-PIB (one of the Computer Security Incident Response Teams, known as CSIRT).

If you come across material depicting child sexual abuse online, you can (and should!) report it without compromising your privacy. How can you do this?

- Dyżurnet.pl: This is a team at NASK-PIB that accepts reports of illegal content. You can use the form on their website. All you need to do is provide the address of the website with illegal content. Reports are completely anonymous—providing your email address is optional (although if you do provide it, you will receive feedback on the steps taken). Go to https://dyzurnet.pl/zglos-nielegalne-tresci and report the content.

- Aplikacja mObywatel: Since November 2024, as part of the “Safe Online” service, a feature for quickly reporting illegal content (including CSAM) has been available. It is a modern tool that each of us has in our pocket, allowing for an immediate response without the need to install spyware algorithms on our phones.

So we have tools that work purposefully and selectively, rather than mass surveillance of all citizens.

Summary

We must protect children—that is indisputable. But building a system of total surveillance that treats every citizen as a potential criminal is a road to nowhere. It is throwing the baby out with the bathwater.

Online security cannot be based on destroying the foundation of trust that is the privacy of correspondence. As you can see, we either have privacy or Chat Control. These two solutions are not compatible with each other.

Take care of your data, encrypt your messages, and don't let anyone convince you that security must mean living in a digital house made of glass.

View related articles

Lądyn! Jest Lądek, Lądek Zdrój, tak...

Pewnego razu, siedząc spokojnie przed komputerem poznałem Kaję. Dziwny zbieg wydarzeń sprawił, że postanowiłem Ją odwiedzić w Sewilli w Hiszpanii. Podróż swoją zaplanowałem tak, żeby zwiedzić Londyn. Miasto, które stało się rajem bogactwa dla Polaków.

Stary rynek w Łodzi

Jak to na koniec roku, trzeba troszkę ponarzekać. O tym, że Łódź jest innym miastem niż wszystkie pozostałe, chyba nie muszę nikomu już udowadniać. Siedząc przed komputerem zdałem sobie sprawę z kolejnego faktu inności tego miejsca. Nam brakuje Starego Rynku!

Mgliste wędrówki po Łodzi

Jakiś czas temu urządziłem sobie nocne wędrówki po Łodzi. Miasto wtedy wydawało mi się puste, smutne i ponure. W pewien mglisty wieczór chciałem wybrać się ponownie i uchwycić to piękno, które Łódź gdzieś w sobie skrywa.